Innocorner is a space where we have everything we need to hold creative meetings. Office supplies, a large screen, flip charts, lots of walls to use as an idea gathering space, products, components – sourced from the market or 3D printed… One of the meetings is in progress. They are led by the Head of the project with his team. I am a participant. There are already more than 100 ideas on the walls for a specific function or for combining them with each other into a complete product. Looking at them – I’m wonder:

- which of them will turn out to be the one, the best one, and will be selected for the prototyping, testing and, perhaps, introduction into mass production phase?

- won’t the best ideas, somewhere in the way of verification, be accidentally left out?

- how will we know when to stop the idea exploration phase and move on to the next phase?

- which of these ideas has the potential for patent protection?

- who, if any, should be entered as the author of the patent, after all, everyone participates are in the process? How do we do this, so that no one feels left out, while at the same time selecting only those people who had a significant influence on the final shape of the idea?

The answer to these questions is the path of inspiration and the way to create it.

What is the path of inspiration?

Perhaps I can start with what is necessary to build it.

In the first phase of the project, when we are looking for new and innovative ideas, we organize a lot of creative meetings. They are of different nature and supported by tools and methods. Some of them are focused on understanding the application for which we are looking for new solutions

or functionality. Here an invaluable tool is “9 windows“, which allows us to analyze the situation we are dealing with on a flexible timeline and with any perspective of the application environment.

Other meetings are aimed directly at generating ideas, such as using tools like “40 Principles of TRIZ” or “Smart Little People” or moderated brainstorming.

There are also workshops, that focus on finding contradictions as potential sources of strong patents. It is then worthwhile to support yourself with the “RCA+” method, for example.

What these meetings have in common are the ideas submitted by the participants.

At this point, the creation of a path of inspiration also begins.

During any activity related to the generation of new ideas, and in fact before starting it, I remind myself and other participants of a few simple rules that, in retrospect, will prove invaluable in helping to build the inspiration path.

Here they are:

- if possible – present your idea with a sketch,

- use a larger post-it sheet if you need it – prepare several sizes before the meeting

- when drawing a sketch of the idea, use colors, for distinguishing components or other elements that will allow others to understand the idea in the future – crayons work great,

- use cross-references and text to supplement the sketch, this

is great to help understand the intent of the idea, - sign your idea, with your name, initials, nickname – so that the author of the idea can be identified.

During the workshop, the facilitator should remind people of these rules when he sees that someone, for example, forgot to insert his initials. Also during the presentation of ideas, it is a good idea to fill in comments or additional information, that will allow the idea to be properly interpreted in the future. It is good practice for the meeting organizer to make his own notes (e.g. on the back of the idea sheet).

When the meeting is over, the organizer should take care of:

- taking photos of all the ideas in a quality that will allow them to be analyzed later,

- recording them in a catalog that will clearly identify them as the result of the team’s work during this meeting (the date of the workshop organization and the methodologies used will also be useful),

- making a presentation to archive the results of the workshop and

to easily return to the ideas in the future.

Between workshops, we hold votes to select those ideas that best meet the evaluation criteria. I will describe the methods of voting and the criteria for evaluating ideas in another article.

With an archive of ideas and voting results prepared in this way, I can start building a path of inspiration at any time. Here’s how I do it:

- I start with the winning idea, placing it at the end of the path,

- I analyze all the proposals made at the meeting where the winning idea was submitted, which somehow guide me to that winning idea. If I find any, I set them in front of the winning idea on the inspiration path, noting the date of the meeting, the authors of the ideas and the tools that were used at the meeting (you can also bring up the evaluation criteria, which will allow you to see how they evolved during the project),

- I open the presentation with ideas, which is the result of the meeting held earlier. As before, I analyze the ideas, selecting those that lead me to the winning idea or to ideas previously on the inspiration path

- in this way I analyze all the ideas, ending with the ideas from the first meeting,

- I send the inspiration path built in this way to the participants of the meetings, for verification,

- after taking into account feedback from the team, the inspiration path of the winning idea is ready.

One of the most difficult moments in a project is deciding to stop looking for more solutions and implement the one, that was chosen as the best during the last selection. So when to end the search? The answer may surprise you: I never end the process. How is this possible?

First, we use agile methods in the initial phases of the project. At each stage we build prototypes and verify their performance. In this way we gain experience and knowledge. And on these we build new ideas. Each successive loop brings us closer to a satisfactory solution. I can analyze these phases and subsequent variants of solutions with the help of

the inspiration path.

Secondly. If before the industrialization phase, by which I mean the moment of financial commitment to the production process (tools, equipment, machinery), an idea emerges that is much better than the one chosen in the ideation process, a change of direction in the project should be taken very seriously. The cost of not realizing such an idea, compared to the cost of extending the project, can be prohibitively high. Especially if we are talking about a product that we plan to sell on the market for the next 10-20 years.

Third. If, during the industrialization phase, someone comes up with an idea that seems to be much better than the one currently being pursued,

it is worth finding the courage to inform the company’s co-decision makers about it, to give them a chance to decide: whether an expensive but nevertheless change of direction, or the potential for another project in the future. In the second option, it is worth describing and archiving the idea well. I will describe the database, which I call an idea incubator, and other tools that help me in my daily work in another article.

Another nagging question is about ideas, that may be really good, but have been lost somewhere between the evaluation criteria and subsequent votes.

Sometimes, I get the impression that some ideas were rejected and yet I saw a lot of potential in them. I also receive such feedback from other team members.

The methods of selecting proposed solutions, no matter what they are, have a subjective element in them, because people make the choice. When making decisions, they need to understand each idea well, interpret, compare with others and evaluate it. I will list some of the reasons that I see as the main challenges in the idea vetting process:

- the greater the number of ideas, the more difficult the evaluation

– that’s why I aim to group ideas and evaluate them in subgroups, - improper assignment of an idea to a group. If, for example, the group should include only solutions that suppress vibrations, and by chance there is an idea that performs the function of connection through a clip, the idea is bound to be lost,

- insufficient description of the idea, too poor an outline, which makes it impossible for evaluators to properly interpret, understand the concept and, as a result, correctly evaluate.

I can’t explain it, but there are times when I intuitively feel, idea is good, but

I can’t make a case for it at the time. In such situations, I use “wild cards.”

If the author of an idea rejected in the vote, “fights” for its reinstatement, but at the same time the only argument is a hunch, then it is worth using such

a card, which allows the idea to return to the pool of those, that will be further considered. Most often, even before the vote, we agree on how many such cards we can allow. Each additional idea allowed to continue competing, means the time needed for its verification, which the project usually lacks – so you can’t overdo the amount.

It’s easy at this point to forget to add these ideas to the path of inspiration and proper presentations. I have no better advice for this than… not to forget :).

In every project, we come to a point, when the project Head has to decide

to move from the idea generation phase to implementation. Or rather, to the implementation of one of them. How can you be sure that the best one has been chosen?

Best… what does that actually mean? I often hear this term, but after all,

it means something different to everyone. To an engineer, it means that he has delivered all the expected functions in an innovative, manufacturable way. To a sales department, best means a functional product with the lowest possible manufacturing cost, so that it can build a solid margin over the long term. For the marketing department, it could be a technological advantage to win new customers and perhaps markets. For the quality department

it could be, product reliability and high repeatability of process steps.

Since this is the case, a method to objectivize the process of selecting the best idea should be to collect criteria from all departments involved and use them during the evaluation process. These criteria will influence the path of inspiration. Once the criteria have been selected, it is worth looking at them and considering, whether they will have the effect of limiting the sources of inspiration. Sometimes it is worth reformulating a criterion to reduce the negative impact, or exclude it from at a particular stage of the project.

This is the way I have been using for many years, keeping in mind, however, that not all criteria can be applied at every stage of evaluation. And if for some reason we want to do so, it is worth introducing weights, that for each criterion can change over time. For example, at the initial stage of the project, a high weight can be given to the level of innovation, and a low weight to feasibility. During subsequent votes, the weight of feasibility should increase.

This way allows us to indicate the final, best solution we want to pursue, with minimal risk, that someone in the company will challenge this choice.

I have another observation about so-called best ideas. Personally, I have not encountered an idea that, from the moment it appeared on the page as

a sketch, delighted all team members and was the obvious solution for everyone or at least most people in the company.

Looking at the history of great inventions and their authors, too, it is easy

to see that the final product or process we know today is the result of many optimizations, trials, failures and successes. I’m writing about this because it’s worth remembering, that behind the success we can observe in advertising campaigns showcasing new products are people who, like us, have come a long way, starting with a sketch on a piece of paper….

One more question remained, which I asked myself at the beginning. Which of these ideas has the greatest potential for strong patent protection. Strong, meaning one that is difficult to bypass. In fact, I have yet to come across an idea that cannot be protected by a patent, except in obvious cases, such as the wheel, for example. It is worth remembering that:

- to estimate the strength of a patent, you need to analyze already existing patents, so this should not be a limiting criterion when generating ideas,

- when preparing a patent application, you can “build up” the strength of the security together with your lawyers. This is a process in which I invest time, because the result may be what I am looking for – the power of the patent,

- patent is a confirmation of the originality of the solution, a sales asset (although not always) and a hindrance to potential competition. However, it is temporary in nature, and competition does not sleep… So patenting should be a permanent part of the design process.

Summary:

- I start building a path of inspiration already at the stage of preparation and implementation of the first workshop,

- it is worth setting aside time in the final part of the meetings to discuss ideas, add comments, add sketches, so that you can easily return to them in the future without losing understanding of the essence of the idea,

- preparing a summary presentation after the workshop is excellent for later building a path of inspiration,

- using the path of inspiration, I know who is the author(s) of the patented solution,

- the process of finding the optimal solution never ends,

- the best ideas that have been described in an unreadable, ambiguous way unfortunately have a good chance of being rejected in the verification process,

- for ideas, that I intuitively think are valuable, but which were rejected in the evaluation process, I use a “wild card”,

- by inviting key partners to the process of creating criteria for evaluating ideas, I reduce the risk of missing out – so-called – best idea.

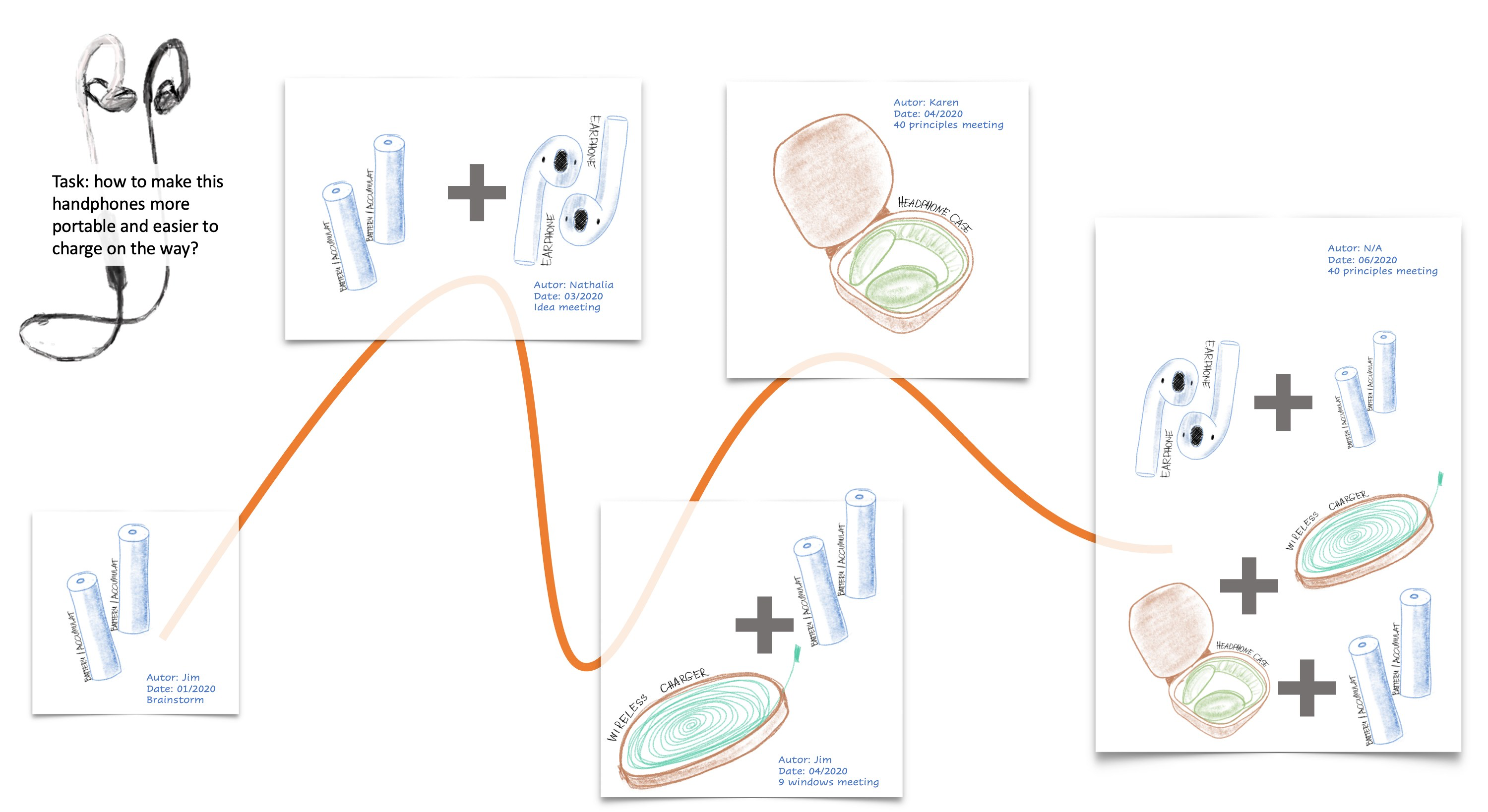

Example of inspiration path – very hypothetic inspiration path, shows how one idea can influence creation of the others.

Leave a comment