Often, when deciding to start a new project, we face the following dilemma:

- should I modify something I know

- or should I invent a product from scratch

This is followed by other questions:

- which of them will be unique and, as a result, allow for a higher margin (price perspective)

- will market interest in the new product cover the expenses incurred (necessary investment perspective)

- how difficult/easy will it be to “copy” it (technology perspective, but also the “strength” of patent protection and cost optimization)

- …

How to start project activities, so that they are focused on solutions that meet the above criteria from the very beginning?

The concept of the ideal solution comes to the rescue.

As with most creativity-supporting tools, in this case too, everything starts with the perspective adopted.

Before I move on to a specific example, I will briefly describe the method.

The main assumption of the Ideal Solution Concept is the starting point of the project. The method assumes two possibilities:

- we find an existing solution that is closest to the desired solution, and the goal of the project is to optimize this solution, by eliminating its flaws and adding the desired functionalities, or

- we define the characteristics of the ideal solution—we can tentatively call the list as specification of the ideal solution, and the goal of the project is to come up with a new solution that meets the specification.

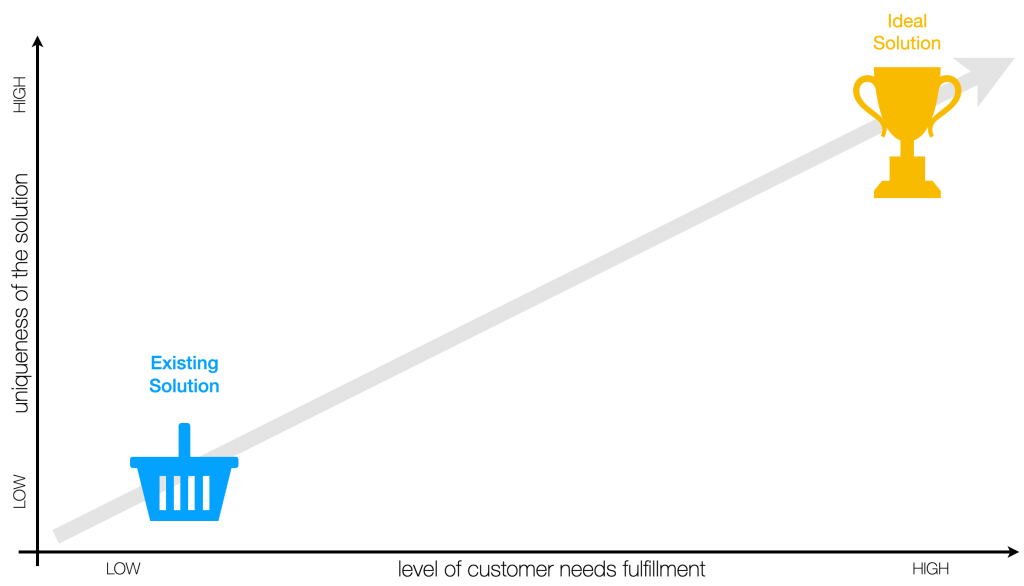

Both points are shown in the figure below:

The final solution lies somewhere between these two points.

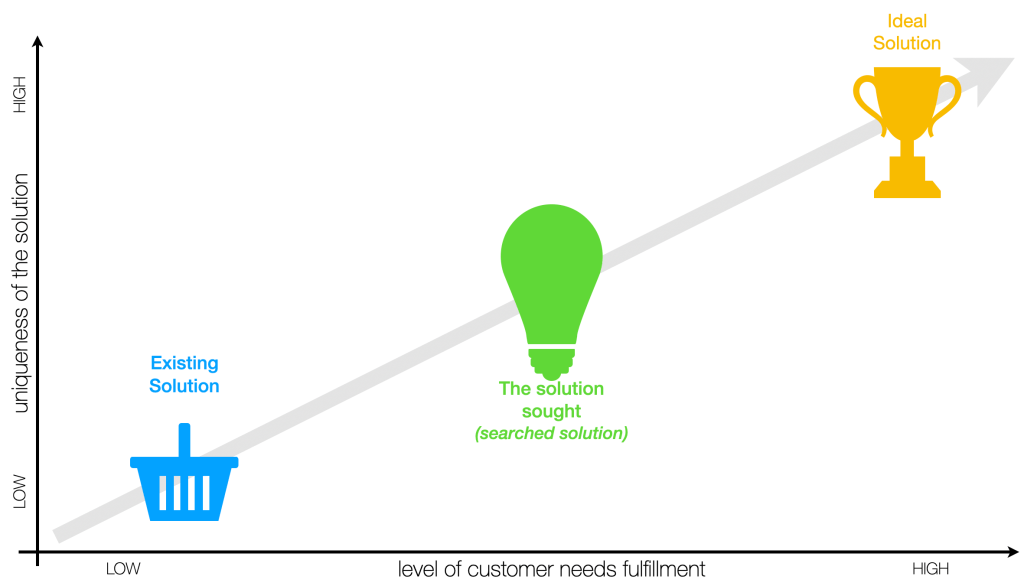

The experience of companies that use this method (including my own) shows that, depending on where we start the design work, the final solution will be more or less distant from the ideal. As schematically shown in the figure below, solution B will be closer to the ideal than solution A, which in turn ensures a higher level of innovation and fulfillment of more customer needs.

(How?) Why does it work?

Regardless of the starting point (A or B), during the design work, teams will face situations in which they will have to make choices. The difference is that:

- when optimizing an existing solution, the challenge is that all functions, shapes, and interfaces already exist—in this case, the compromise (or the desired balance) will involve limitations resulting from what already exists, and will consist of choosing those functionalities, that the current design allows, so not necessarily those that we planned to implement.

- When coming up with new solutions, the only limitations will be the team’s creativity, the available technologies, and the limitations that are common to both – broadly understood resources.

However, this does not mean that the concept of an ideal solution does not need existing solutions. They can be an inspiration for design teams and a source of knowledge, confirmed by customers, about what does not work as planned or what expectations are not met.

Example.

A customer contacted the company I worked for and asked if we could offer a solution for one of the new products in their portfolio. The challenge was to meet technical requirements that were unusual for our products, but above all, the short deadline for starting mass production. It was the time pressure that meant no one even thought about starting the project from point B… Looking back, I cannot say for sure whether, under those circumstances, we would have been able to complete the project on time, starting from that point, i.e., aiming for the perfect solution. One thing I know for sure. The project was ultimately successful. The customer received the solution on time. However, it quickly became apparent that the solution required further modifications.

In the case of new technologies and their applications to new applications, the most important thing that design departments focus on throughout the development process is a working product. Its manufacturing cost in the early stages is secondary. The product must work. However, when production volumes change from hundreds to thousands and then to millions, cost pressure immediately arises.

This was also the case here. The prospects for sales growth and the resulting cost pressure forced us to return to the design work. And again, we were faced with a choice: start from point A or B…?

Why did we face the same dilemma again in a relatively short period of time (about 2-3 years)? If we had started working from the other side of the curve described above the first time around, would the situation not have repeated itself?

Today, I am sure, that it would not have happened again. After just a few months of working on the first solution, we noticed that:

- the product we offered was oversized in some aspects, so it required cost optimization,

- and in some aspects it did not meet expectations, which made it necessary to add further functionalities. For the project team, it was a new application for this type of product, with different working conditions, a different testing method, and specific evaluation criteria. As a result, all the “oversizing” issues – associated with increased costs – remained. Additional necessary functionalities were added to them, which also increased the cost of production. In addition, when combining existing and new functions and features, it turned out that they did not always “work together”, which resulted in additional challenges. As I mentioned earlier, the working solution was delivered to the customer on time. However, the decision to modify and optimize the existing solution for the needs of the new application was not successful in the long run. Therefore, my team and I were once again faced with a challenge that was a kind of “déjà vu.”

I once read that: if you do the same things in the same way, you can hardly expect different results… so this time we started from point B.

How to get started?

Defining the ideal solution.

When I work with a project team that has not defined the ideal solution before, I often start with a simple exercise that helps them understand the essence of the process and “enter” into a mode of open and creative thinking.

Exercise.

To conduct the exercise, you will need a flip chart and a pen.

The exercise begins with the question: This is a pen. What features can you add to it to turn it from an ordinary pen into the ideal pen?

The first functions that come to mind are usually those that the participants have already seen in other pens (which is completely natural). I write down all the suggestions on the flip chart. Here are a few examples of the most common answers:

- a choice of several colors to write with

- erasable ink

- a built-in laser pointer

- etc.

After writing down these few examples, there is usually a pause and the meeting participants look at each other with a questioning look: what else could we suggest? This is an important moment in the exercise. As the moderator, I ask questions that are designed to open up new perspectives:

- Who uses or could use a pen? What functionality comes to mind when you think about these people?

- In what circumstances do we use a pen, and in what circumstances could we use it if it had… well, what exactly?

After these types of questions, the team no longer sees the pen in my hand. People are not trying to remember what types of pens they have seen. Now they are using their imagination and beginning a creative process. More suggestions are made, which inspire new ideas.

My role is to encourage the opening of new perspectives. The team’s role is to come up with needs and ways to meet them.

Some of the ideas are in the “science fiction” category. These are important ideas. The meeting is a brainstorming session, so we don’t judge them. The important role of ideas often described as “unrealistic,” “unfeasible,” or “exaggerated” is to encourage the team to abandon “natura”’ and “everyday” evaluation criteria, limitations, and ways of thinking. They also inspire new ideas, which often fall into the category of original, unique, interesting, and importantly, feasible ideas.

At the end of this exercise, I read the complete list of ideas from start to finish. I draw attention to their nature and the time they appeared. From the obvious, through the unfeasible, to the original, unconventional, and pioneering. This reflection is valuable and can be referred to when the team is working on a real challenge.

After this exercise and a short break, you can start working on defining the ideal solution in a real project. The role of the moderator is the same as in the exercise described above. The team is now open and ready to propose non-obvious needs and solutions. Inviting people from other departments to an extended project team meeting will certainly help to open up more important perspectives and, as a result, define a product/process closer to the ideal solution.

The result of this meeting is a practically complete specification of the ideal solution. Now you can move on to:

- generating ideas, more information in the articles “Where do good ideas come from” and “The recipe for a good idea”

- Building hypotheses and confirming them

- enjoy Rapid prototyping

Leave a comment