The R&D department’s project portfolio is systematically reviewed and supplemented. The impulse for verification may be a completed project, a meeting with a customer, or a significant change in the market situation.

The portfolio is a kind of roadmap that indicates which areas of the market are or will be the source of the company’s profits in the future. Who should be involved in the portfolio creation process, what is their role, and what should they provide?

I will briefly describe the roles that seem to be the most important and necessary for creating a valuable portfolio.

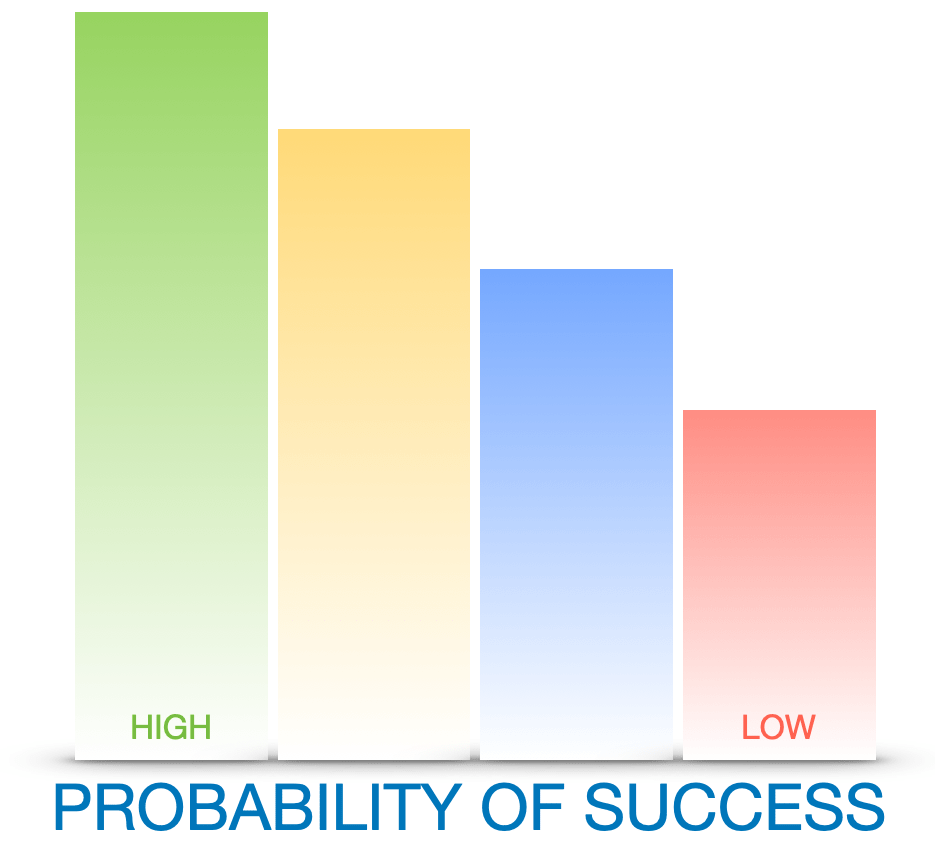

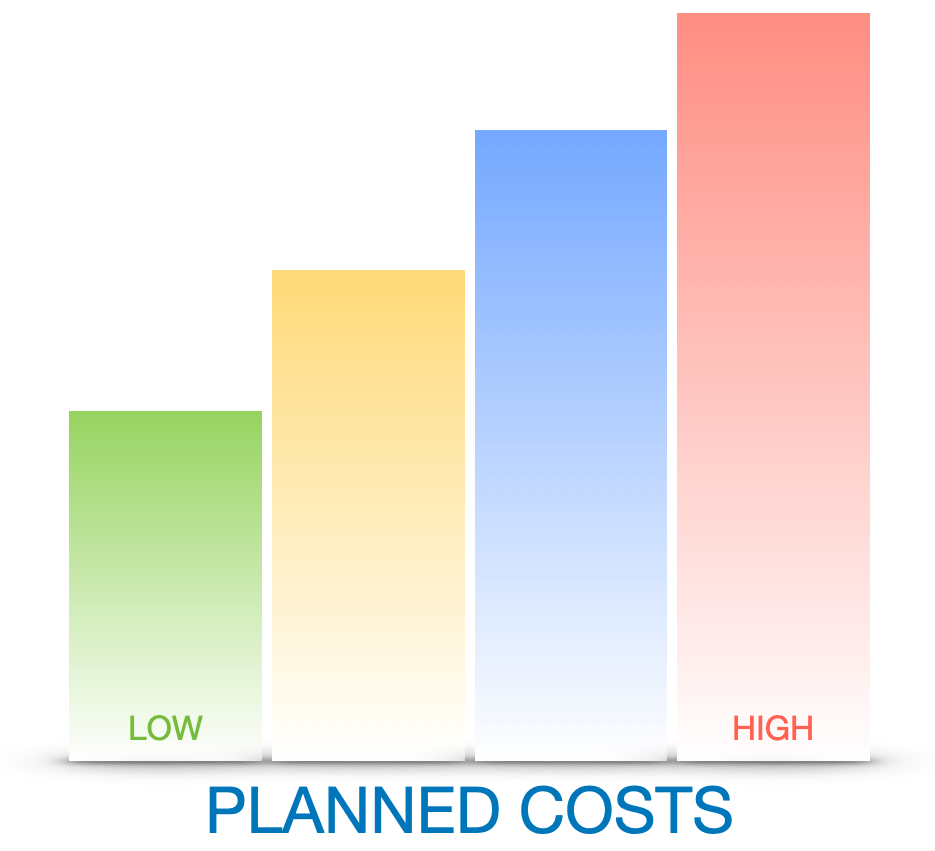

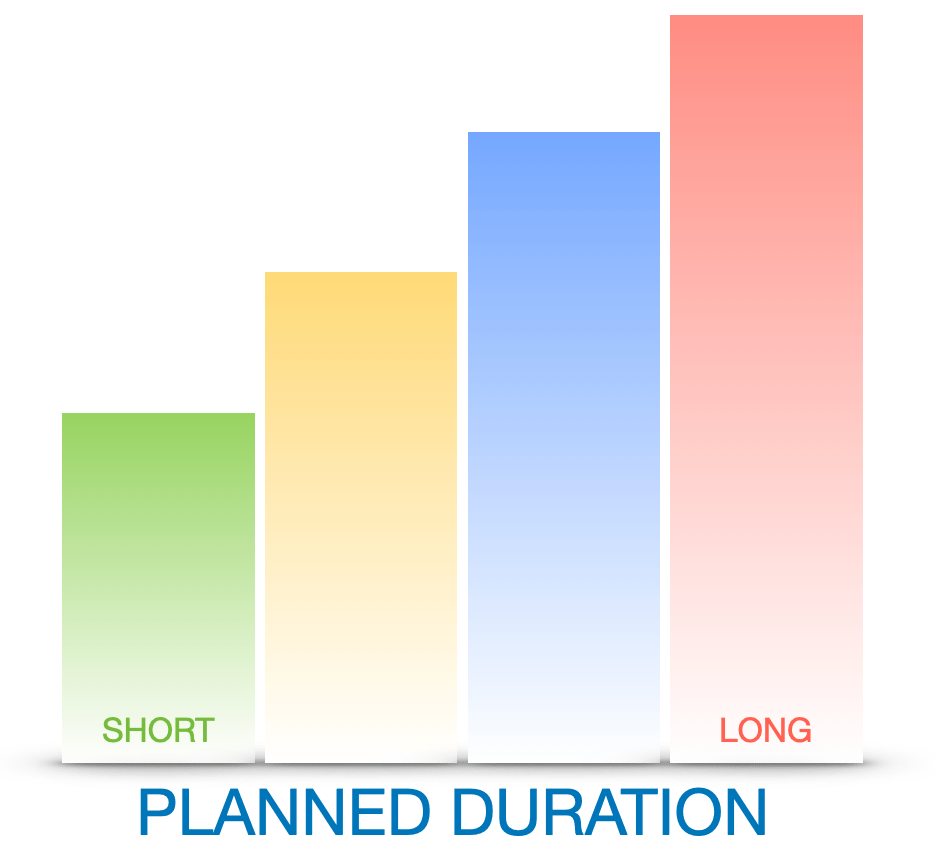

A strategic role responsible for defining types of innovative projects aimed at creating new products in the companies’ offerings, known as NPI (New Product Introduction) projects. This division is critical to maintaining transparency in the differentiation of projects based on their purpose, expected level of innovation and profitability, planned duration, level of planned costs, as well as chances of success/possibility of failure. Examples of job titles that perform this role: Innovation Portfolio Manager, Innovation Strategy Lead, R&D Portfolio Architect, Head of Innovation Classification.

Another strategic role involves setting development goals for a selected application, product, or market segment. The person in this role works closely with or is part of the sales and/or marketing department. They know the history of the selected part of the product range and the main competitors, and follow megatrends and changes in the strategies of key customers. They have their own vision and direction for the development of this area, supported by external and internal analyses. They understand the technical and commercial aspects of the application, as well as the short- and long-term needs and plans of related industries. They have a constantly updated list of products and functionalities that they want to introduce into their area in order to increase competitiveness, attractiveness, margins, and respond to emerging new market needs. Unlike the previous role, which is (usually) performed by one person in the company, this role is usually performed by at least several people. The more extensive the company’s product portfolio, the more people are involved. Examples of job titles that perform the described role: Product Development Leader, Segment Development Manager, Application Strategy Manager, Business Area Development Leader, Head of Application Strategy, Market Segment Manager.

The third role is the decision-making role. This can be one person or a group of people. This role should be well informed in the company’s global strategy, its values, and its economic situation. Its main task is to select projects for the product portfolio, which are then implemented by the R&D department. The company’s management must be involved in the decision-making process. It can do this directly, by selecting projects itself, or it can delegate this task to a person or group of people, while communicating its expectations, which I will discuss in a moment. Examples of names of groups that perform this role include: Innovation Steering Committee, Product Portfolio Board, Strategic Project Selection Board, Portfolio Governance Team, Executive Portfolio Committee, or individual positions: Chief Innovation Officer (CInO), Head of Product Portfolio Strategy, VP of Strategic Innovation, Portfolio Strategy Director.

We already know the main participants in this process. Let’s consider how they cooperate with each other in practice. What information do they need from each other, and what happens when they don’t receive it? For the purposes of this article, I will refer to the individual roles as: Innovation Portfolio Manager (IPM), Head of Application Strategy (HAS), and Innovation Steering Committee (ISC).

STEP 1 – project classification criteria

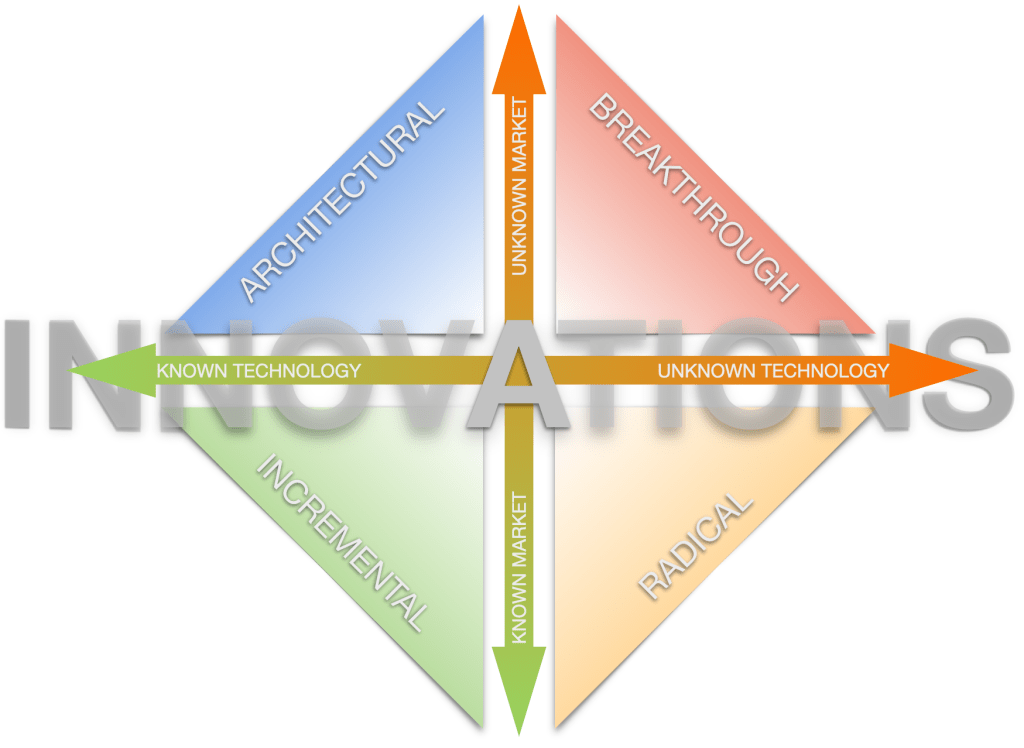

A prerequisite for creating a portfolio is to define the types of projects and all the consequences associated with them. The classification I often use divides innovative projects into four groups using two criteria: market/customers/applications and technology. As a result, we obtain projects of the following types: incremental, architectural, radical, and breakthrough.

Below, I have presented each of the five characteristics mentioned above in such a way as to show the difference between the types of projects. The colors correspond to the type of innovation project (incremental, radical, architectural and breakthrough).

Creating a clear division and valuable evaluation criteria is an important task for IPM. It is equally important to present this division to all participants in the project portfolio creation process, as well as to all members of the project teams. It is crucial that everyone has the same understanding of the differences between project groups – both among board members and engineers or project leaders. The education process is ongoing and should be part of employee onboarding training.

STEP 2 – Organized list of project proposals

The task of each HAS is to continuously update the list of potential projects that should be implemented from the perspective of the managed part of the product portfolio. These projects should be assigned to project groups defined by IPM.

In addition to the aforementioned identification (project type), this organization should also include a parameter of importance and urgency (or at least one of them). A list or matrix constructed in this way is essential for the work of the ISC.

STEP 3 – updating the product portfolio

In order for the ISC to effectively fulfill its role, it must receive clear guidelines from the company’s management regarding the strategic directions of the company’s development. These include:

- Determining the level of financial risk the company is willing to take in relation to its projects, i.e., the percentage of the budget allocated to innovation, taking into account the types of innovative projects (incremental, architectural, radical, breakthrough)

- Identifying market areas in which the company wants to strengthen, maintain, or withdraw its presence, i.e., determining the percentage of projects (or percentage of the budget) related to optimizing the existing product portfolio in relation to seeking solutions in new, unknown markets, in the area of new applications (from the point of view of the company)

The management board may provide more guidelines, bearing in mind, however, that they cannot be mutually exclusive. An example of such guidelines may be, for example, the expectation to design a product for a new application, in a new market segment for the company, in the time needed for incremental innovation.

Below, I describe several examples of situations in which the roles mentioned do not exist in the organization or do not fulfill the described function.

Example 1.

The company does not have a clear identification of project categories and the resulting consequences.

The lack of categories for innovative projects is evident at every meeting concerning innovation. It does not matter at what level in the company hierarchy such a conversation takes place. Each person participating in the meeting, when commenting on the same project, has a subjective idea of the expected level of innovation, profitability, costs, duration, or likelihood of success. The project has not been assigned to a category (because categories do not exist) that clearly reflects the aforementioned characteristics of the project, which often leads to opportunistic expectations: sales require quick availability of the product in the portfolio, management expects complete success with a minimal budget, quality requires full validation and alignment with customer requirements, R&D time and resources that are not consistent with the expectations of the listed stakeholders. Such an atmosphere is not conducive to quick agreement. Each time, the process of “reaching” expectations and the possibilities for their implementation starts from scratch. The compromise reached often does not stand the test of time, and what was approved at the initial stage is questioned by various parties at each stage of the project implementation (as time passes, opportunistic goals change). This poses a major challenge for project teams, who in such conditions do not really know when a completed project will be considered a success and when a failure.

Example 2.

The Head of Application Strategy does not have a list of the most needed products and functionalities that should be introduced first in the application area they manage.

Let’s imagine a situation in which the R&D department completes one or more projects and will soon free up resources for new ones. In this situation, the Innovation Steering Committee asks the Heads of Application Strategy for proposals for projects that should be implemented. And they don’t have any…

It is difficult to imagine a situation in which R&D employees will not be working on another project, so the process of searching for “candidates” begins. Time is short, so most people asked what the next project should be about respond by again (why not?) being opportunistic, responding to the needs of the moment, drawing on conclusions from the last meeting with the client, experience from the previous project, their own ambitions, etc.

Let us recall the key elements of the role of Head of Application Strategy: “Knows the history of the selected part of the product offering, main competitors, follows megatrends, changes in the strategy of major customers. Has their own vision and direction for the development of this area, supported by external and internal analyses. Understands (…) the short- and long-term needs and plans of related industries. (…)”

When we compare this with the opportunistic choice of another project, devoid of all the above-mentioned qualities, we can conclude that this project, from the perspective of the entire organization, has little chance of success from the very beginning.

Example 3.

The Innovation Steering Committee did not receive clear evaluation criteria from the management board or received criteria that are mutually exclusive.

Returning to the previous example, let us assume that the Innovation Steering Committee received a list of potential projects to be implemented. In the absence of evaluation criteria provided by the management board, it will select, to the best of its knowledge, those projects that it considers most justified. There are two scenarios: either the adopted criteria will coincide with the expectations of the management board, or they will not. In the latter case, the project has no chance of success; worse still, it may be torpedoed during implementation by the management board itself.

In a situation where the management board provides conflicting criteria, the situation is even worse, because the Innovation Strategy Committee has no chance of selecting a project in line with the management board’s expectations. Once a project has been selected, the management board will always be able to argue that the choice was incorrect.

I assume that such a situation cannot occur intentionally. It is not in the management board’s interest. However, it may occur when the management board does not have knowledge about the nature of innovative projects and their specifics. And so we return to the first example, which talks about identifying project categories.

To sum up:

- The R&D portfolio as a roadmap – it is systematically updated and indicates the company’s future sources of profit. It is crucial that it is linked to the expectations of sales, marketing, and management strategy.

- Three main roles in the process:

- Innovation Portfolio Manager (IPM) – defines project categories and evaluation criteria (innovation, profitability, time, costs, risk).

- Head of Application Strategy (HAS) – sets the directions for product/application development, creates an organized list of project proposals.

- Innovation Steering Committee (ISC) – selects projects for implementation in accordance with the company’s strategy and management guidelines.

- Key stages of the process:

- Step 1: defining project types (incremental, architectural, radical, breakthrough).

- Step 2: structured list of project proposals with importance/urgency weighting.

- Step 3: Update the portfolio in accordance with the criteria and risks accepted by the management board.

- Organizational risks – lack of clear project classification, lack of a priority list from HAS, lack of clear guidelines from the management board or their internal contradictions lead to opportunism and chaotic decisions.

- Conclusion – only consistent roles, clearly defined criteria, and continuous communication between R&D, sales, marketing, and management allow the R&D department to deliver projects on time and in line with business expectations.

Leave a comment