“We need good ideas” – I’ve said and heard it so many times, that I’ve moved on to what this oft-repeated expectation really means? Just as often I hear the question, “Well, we have quite a few different ideas here, which one is the best?” Well, exactly which one?

The first association that leads me to the answer – I find in… the kitchen. It’s the weekend, I ask the household, what they would like to eat for dinner on Saturday. The standard answer is “something good”. Immediately afterwards I get a different suggestion from each person. A discussion begins, mutual persuasion of each other’s idea, concessions, changing of minds and most often one dish is chosen. It happens that one person doesn’t like this choice and says “I don’t feel like it, I’ll eat something else”.

Let’s look at this situation as a process aimed at choosing a good dish.

The perspective of the duration of each step is not important. The essence of this example is to notice the sequence of steps that follow one another. In fact, in the example given, the steps often intertwine and merge. For the purpose of this analysis, I have deliberately singled them out.

Step 1. At the mention of lunch, most of us feel a slight hunger and begin to think about what we want. I will call this stage a working awareness of a specific need.

Step 2. Everyone begins to ask himself questions: what he hasn’t eaten in a long time and would love to eat, what has he eaten in the past few days? Or maybe he feels like trying a certain dish for the first time? Perhaps he is inspired by the Instagram he has just browsed? It could also be, that the person has a plan for how to spend a Saturday afternoon, and mainly he or she will want it to be something with a short preparation time. Knowing that the end of the month is approaching and the budget situation is tight, someone may propose a dish, let’s call it “tasty and cheap.” I will call this step the stage of identifying individual expectations.

Step 3. Various proposals appear and you have to choose one of them. A conversation begins to explain your criteria for choosing a dish. Given that the example involves a Saturday dinner for a family that knows each other well, one might expect a high propensity for compromise. But imagine, that the choice is about the menu for a wedding party and two families with very different culinary tastes are talking. Such a discussion can be quite long…This stage is to establish criteria for choosing a good dish.

Step 4. This is the stage when the final decision and choice is made, as to what will be served for dinner on Saturday. The criteria are already known, it’s clear who wants what, a few compromises are made. We review the proposals and choose a dish, that the majority will judge as good for Saturday lunch.

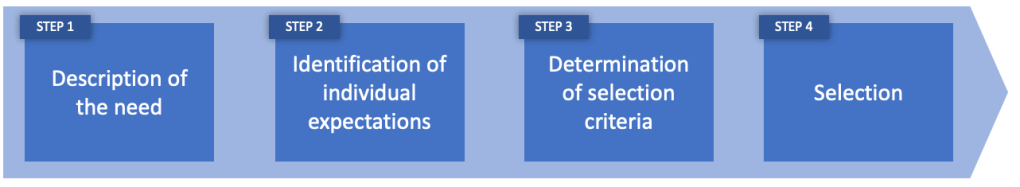

In summary, we have gone through 4 stages:

- Description of the need – in this case, the need to eat something on a Saturday afternoon,

- Identification of individual expectations – everyone had the opportunity to present their needs, preferences, expectations,

- Determination of selection criteria – defining the most important criteria that must be taken into account when choosing a dish

- Selection – the dish was selected.

The situation described above has very many elements in common with the situation of searching for “good ideas”. We can implement the 4 steps listed above to any situation where there is a need for value judgment, e.g.: good vs. not good idea, or good vs. better idea.

Here are some examples of how using a process approach can help identify good ideas.

Step 1. Description of need / Value proposition

Imagine a situation where in a meeting with a team we give a message like this: “We need more good ideas” followed by an announcement, that we will return in a week to select the best one. Such a message raises awareness of the need to work on ideas, but does not specify the motivation, the area, the purpose of the search.

The result of a task formulated in this way will most likely be a collection of ideas, that will be very difficult to compare and evaluate with each other, since they will be related to very different areas of the company. Alternatively, the result will be a lack of ideas, since their purpose is very vague.

The need to seek new ideas should be more specific. The message could be phrased like this, for example: “We are looking for ideas for a product that: will be a successor to product XYZ from our portfolio, will have the current functionality (must have condition) as well as additional functionality ABC, that results from the expectations of our customers, and is feasible within the known and currently used technologies in our group. Moreover – we plan to launch its production in the next three years.”

If one were to try to compare the two tasks on one numerical axis, I would place the first one on the left near “1” as a very poorly realized and very unspecific need, and the second one on the right – above “10” – as a conscious and very specific need.

Before delegating a task for implementation, it is worth considering where on this axis is my description of the need. How well do I understand it, what do I expect? When describing the need, do I use general or specific terms? Have I highlighted the main features that future ideas should include? Have I divided them into critical ones (must have) and those I care about (nice to have), but not including them will not be disqualifying when evaluating ideas? Are my expectations consistent, or are they mutually exclusive? And very importantly: how do other people involved in the project understand this description. Every word matters. An additional challenge can be working in an international team that, as in my case, uses English in official communication. Individual words are not always understood in the same way, so it is important to jointly agree on the description of the need.

An important comment on expectations, that are mutually exclusive or, to put it another way, contradictory. If the team feels that both expectations are crucial to the final success of the project, they can be left in the description, noting their mutual relationship. As H.S. Altshuller, creator of the TRIZ methodology, says, all significant patents in the history of the world resolve some contradiction. This is quite a challenge worth taking on, and one in which the project team can be supported by the contradiction matrix and the 40 principles of TRIZ.

I see a big correlation between the level of awareness of the need at this stage and the final evaluation of ideas. Lack of specific expectations, usually leads to a situation where it is difficult to talk about good ideas – because no one knows what it really means.

Needs can also be called values, which ideas should deliver to the final solution (value proposition). In the article I will use these words interchangeably. Since the value proposition is defined, the phrase good idea takes on a specific meaning. Now everyone knows what should be included in an idea for it to be defined as “good.”

There is another risk associated with the definition of good ideas. It appears most often in projects that last several years (e.g., 3-5). Needs defined at the beginning of a project can – and most often do – evolve. This is a natural phenomenon. As the project progresses, contacts with clients, subsequent prototypes and test results, market analysis, the project team may modify the result expectations of the ongoing project. Therefore, it is good practice to revise the value proposition to be delivered by the team, at least when moving to subsequent milestones / levels of product maturity. The consequence of these changes may be changes in the duration of the project or the cost required to complete it.

This stage, by its nature, must be implemented first. It defines the scope of the other steps.

Step 2. Identifying individual expectations

I’ll use the example again with the need to search for a new product described above. If we ask people from different departments what they expect from a new product, they are likely to vary widely. From weight, cost, technology used, reliability, innovation, packaging efficiency, scalability of the solution, to optimal supply chain and minimization of carbon footprint. Their diversity should not discourage us, on the contrary. These expectations can provide additional inspiration for the project team.

If we imagine for a moment, that we have not asked one of the key departments about their needs, we can assume that:

- the chosen idea will potentially be “incomplete” because it may not include a key functionality, feature,

- they will potentially be among the first people to challenge the selection of the final idea as “good.”

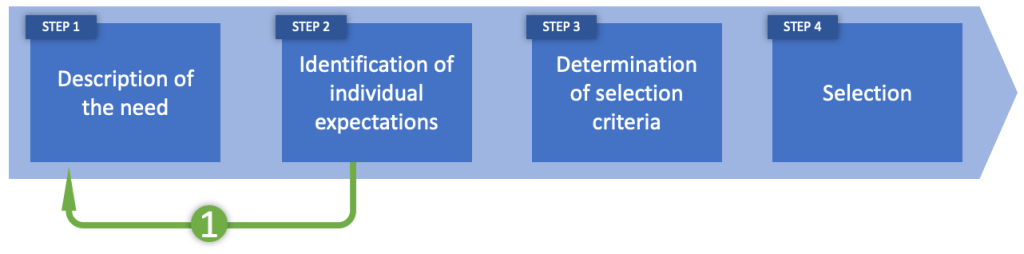

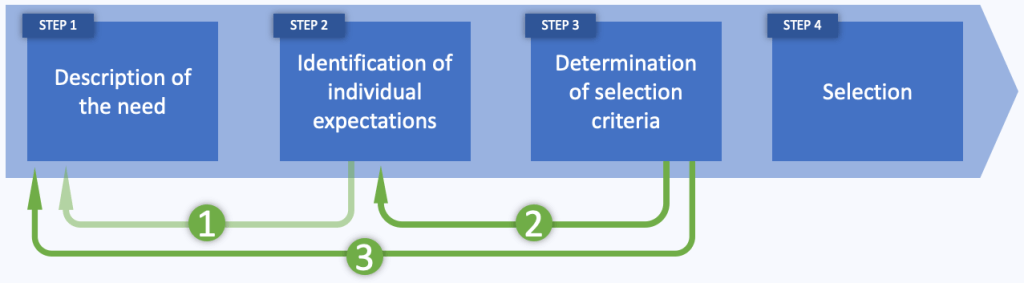

Is it possible to start with this step? If I try to imagine, how I would answer the question about my needs, without knowing what they should be about, it is rather difficult. However, this stage is a good opportunity to clarify the description of the need and move it on an axis closer to the “10”-s. That’s why, it’s a good idea to go back after this stage and revise the description of the need.

Step 3. Establishing selection criteria

The stage of setting criteria is the next step in the definition of a good idea. As in the previous steps, it should not forget the impact of time on the project team’s awareness. That’s why it’s a good idea to review the criteria in a similar way to expectations, for example, as you go through successive milestones in the project.

An additional challenge is the limitations of not being able to apply all the criteria, at every stage of idea verification. Very often, the result of the first creative meetings are partial ideas (defining a single function), not fully defined (proposing the use of a mechanism but not defining a material, or vice versa), or are focused, for example, on the assembly process without going into the structural details of the product. The selection criteria should help the project team promote those, that support the key values written in the need description (value proposition) and eliminate the others. For this to happen, they must be properly defined for subsequent development loops.

Two examples of criteria that, in my opinion, should not, and often appear on the list of criteria for the selection of first ideas.

The first is manufacturing cost, the second is manufacturing feasibility. Given that at this stage ideas are only partially defined, it is impossible to reliably estimate both of these parameters. I want to emphasize, that these are very good criteria, but to be used in a later phase of the project. In the initial phase, I would suggest using others, such as patent potential (the level of innovation from the point of view of a particular company and the technological knowledge of the team) or design feasibility (whether the team sees potential chances for the idea to work from a design point of view).

Criteria that should necessarily be on the list of any evaluation of ideas regardless of the phase of the project are those in the critical value group (must have) and optional (nice to have). If the answer to such a question directly is not straightforward, it can be phrased as follows: “Does the idea in any way bring me closer to the critical or optional values?” If the answer to this question is yes, it is worth promoting the idea to the next stage.

After building a list of selection criteria, it’s worth compare them with individual expectations and then with the description of the need, and making sure that all three definitions are consistent and lead the team to generate and select “good ideas.”

Step 4. Selection

Assuming that the previous steps were done correctly, the selection of “good ideas” should be relatively easy and not controversial among team members.

A topic for a separate article is the method of selection of ideas, the method of evaluation (comparative, quantitative/qualitative), grouping of ideas before voting, preparation of the team for voting (calibration). These aspects can also affect the final selection. However, I believe that 80% of the impact on the final result is due to the 4 steps presented for selecting a good idea, while the method of selection has the remaining 20%.

Summary

I wonder if there is another way to unravel the mystery of selecting a “good or best” idea….

The one described above seems to be very transparent and taking into account the interests of all concerned. By choosing the weights of the criteria, we can consciously “control” the level of risk, the time of implementation, the amount of investment, the innovation of the ideas selected.

In this way, we give meaning to “good ideas” and avoid the risk of different interpretations by defining them collectively.

Here are some selected criteria for evaluating ideas, which I have developed working with various teams and support the process of selecting valuable ideas.

- Meets the main needs of the project (value proposition)

- Has the potential for a strong patent – the greater the potential the more valuable the idea.

- Has positive feedback from potential customers – for example, they want to test it on their application, or they want it to be part of their development process, validation plan. If the customer says: “Oh yes, I like it but…”. – then I have to listen carefully to what he says after the word “but”. This is most likely my next challenge,

- Have the approval of the – widely understood – project team

-

[…] generating ideas, more information in the articles “Where do good ideas come from” and “The recipe for a good idea” […]

LikeLike

-

[…] budget and quality. In practice, this usually boils down to choosing the best idea (see article “Recipe for a good idea”) for a product and then making that vision a reality by preparing the necessary documentation. What […]

LikeLike

Leave a reply to The concept of the ideal solution as the starting point for the project – R&D Coach Cancel reply