Confirming and disproving hypotheses is one source of knowledge acquisition (but also creation) for the development team. These sources can be divided into internal and external. The first is the company’s output. Capitalized knowledge, results of tests carried out during already completed projects, knowledge of applications – to which the company supplies the developed and manufactured products.

External sources are potential customers, previously unknown suppliers, institutes, universities, external laboratories, consulting companies, patent databases….

Internal sources are usually a sufficient body of knowledge, for teams that are involved in two types of projects: the delivery of a defined function by the customer, through a set of specifications that, on the one hand, guide the project team towards the final product and how to test the performance. On the other hand, however, they are a significant constraint on creativity and decision-making freedom, as each must be approved by the Customer. The second type of project is incremental innovation.

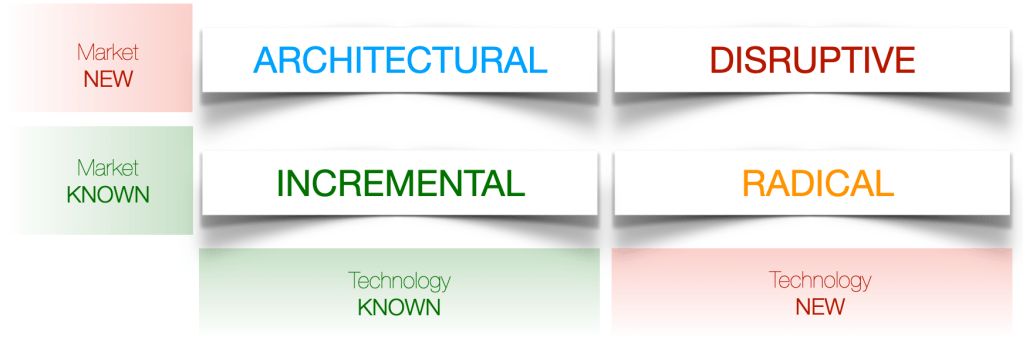

In illustrating further types of projects for which internal sources of knowledge are absolutely insufficient, I will refer to the well-known division of innovation projects.

It presents 4 types of innovation projects (Incremental, Architectural, Radical and Breakthrough) that a company can opt for. Each of these is defined by two parameters, represented on axes – Market and Technology. In order to assign a project type to one of the charts, we can take the point of view of a particular company. This means that a project with the same scope and goals, for example, may be an incremental project for one company and a radical project for another. In this case, we can speak of the subjective nature of the assignment. We can also take the perspective of all known market players and thus determine the type of project. Then the attribution will be more objective, but also more difficult to assess the effort a company has to invest in its implementation.

For the purpose of this article, I will take a subjective approach, i.e. describing the perspective of a specific company (not the entire market).

Each parameter can take on two values – „new” and „known”.

The market from the point of view of any company can be „known” or „new”. „Known” is the one in which the company has already operated and/or is still operating. It is the list of customers to whom it currently supplies products and/or services. It is also a good understanding of the needs and problems of existing Customers. An „new” market is all the rest of the market.

Technology similarly, can be „known”, i.e. the company understands and owns the technology it uses in the processes of creating products and/or services. It employs staff who consciously maintain it to currently known standards in the market. Technology can also be „new”, meaning that the company does not currently have any internal or external resources to use it.

Now I can move on to projects, that absolutely need external sources of knowledge. As you can easily guess, any project for which at least one of the above parameters takes the value „new” is such a project. Innovations for which both parameters are „new” – the so-called disruptive – are the most demanding and difficult, because in their case the company has to acquire/complete knowledge both in the area of technology, as well as potential customers and their applications (in the sense of product and services). Compared to incremental innovations (projects), also those named as architectural and radical are the ones that need external sources of knowledge. Without going into the details of how to establish relationships with potential customers and suppliers in the very early stages of development – and this is often a long process that requires close collaboration between R&D, Marketing and Sales – I will get to the essence of this article.

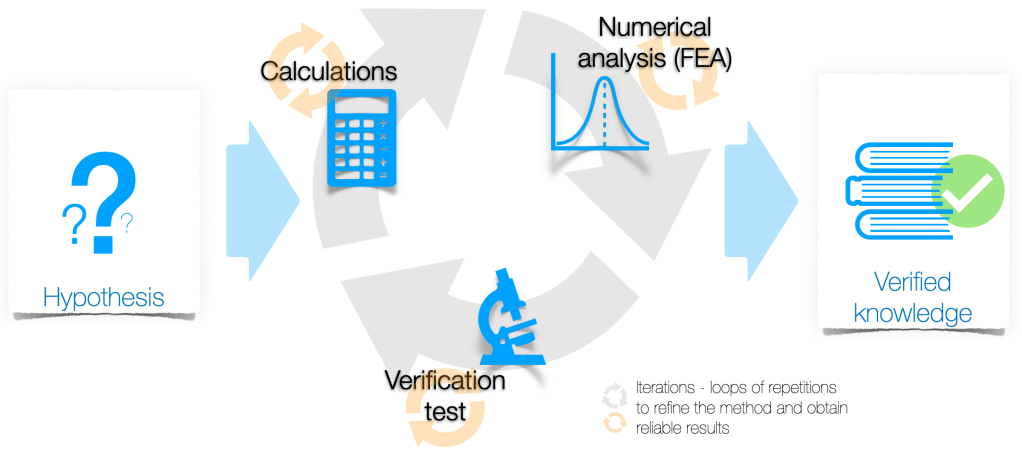

Let’s assume, that we have already developed and defined knowledge acquisition channels. We have acquired and are acquiring further information, about the application to which we plan to deliver a product or service in the future. Often this information will be residual, inconsistent or mutually exclusive. In such a situation, what can the project team do? It can use the hypothesis verification triangle.

As the name suggests, this model has three stages, that form the vertices of the title triangle.

These are sequentially: preliminary calculations, numerical analysis, (physical) verification test. These three stages are preceded by the definition of the hypothesis that will ultimately be confirmed or refused.

At this point, it is worth outlining the situation of a design team working on an architectural innovation, especially a radical or disruptive one. They are working on a product (or service) that does not exist in their company’s portfolio (product catalogue). What they are working on is unlikely to be similar to anything already in that portfolio. All previously trodden paths of calculation and estimation of performance do not work. It is unclear what to test and how to test it – after all, it is a product that is part of an application, they do not yet understand. When they specify the physical size they plan to test physically, it turns out that there are no such devices in the laboratory and external suppliers expect to specify the test procedure. The components and materials needed to build the first prototypes are unavailable in the portfolio of current suppliers, they have to find new ones – who also expect specifications of what we want to order – and they are missing. In short, the area of unknowns and the issues, that need to be defined and prepared to verify further hypotheses are enormous. These are the daily challenges faced by R&D teams working on the innovation projects mentioned earlier.

It is therefore essential, that successive hypotheses are verified in a structured way that helps to ensure efficient use of resources while capitalizing on knowledge.

Each of the three stages is iterative (repeated loops – see figure above). The number of iterations depends on the team’s decision. If they conclude, that the next stage should be a test – they plan to perform the test. If they decide that a numerical model needs to be built to verify the hypothesis – they plan what is needed to do it.

The essence of the hypothesis verification triangle is to compare the results that its successive vertices generate.

The team should determine at the beginning of the project (if there is no such determination at a global level) what level of correlation between the different stages will be considered sufficient, to allow a decision to confirm or refute the hypothesis. Failure to achieve this level between all stages, will result in the need to go back to each stage and consider why the correlation has not reached the expected level.

Only achieving a sufficient level of correlation allows the results obtained to be used in subsequent design steps. Getting this level is seen by the team as confirmation, that what they have calculated, verified in numerical analysis and physically tested is consistent. In this way, they confirm that they have built up a „piece” of new knowledge, that they can use in a current or future project. In doing so, they reject test methods, FEA models and results that, due to lack of correlation, could be completely misleading and lead to false conclusions. These, in turn, to wrong decisions and consequently building a product, that does not meet the design goals and, most importantly, the expectations of potential customers.

Ideally, all three „vertices” should achieve a sufficient level of correlation. However, I allow for the simplification of correlating two „vertices” – provided that one of these steps is a physical verification test. This is particularly justified in cases, where preliminary calculations or numerical analysis is practically impossible from the point of view of available knowledge, skills, tools (available licenses). In such situations, significant simplifications would be required, which in turn could be the source of large discrepancies.

Simplifications in the construction of new knowledge, that rely on the results of only one stage (vertex) are very dangerous, due to the very high uncertainty they are subject to. As a rule, they should be rejected by the project leader or verified by a second, different „vertex of the triangle”.

Challenges in applying this model:

- The ability to formulate hypotheses, that bring the team closer to the project goal – a misplaced hypothesis can lead to erroneous conclusions, so it is worth reviewing the content of the hypothesis with the wider project team at this stage.

- Systematicity and persistence in the face of available time on the project – there may be a temptation to take a „shortcut” and not use this model, especially when available resources are severely limited. I am not saying that it is not possible to do this. What is important, is that it’s a decision of the whole team (core team) based on a transparent and illustrative presentation of the risks involved in such a decision.

- Consistency – it is sometimes possible to encounter „resistance” from a team, that does not see the added value in confirming the results obtained from one „vertex” with another test. What can prevent such a situation is for the project leader to define the way of working for hypothesis verification at the beginning of the project.

- Choosing a 1, 2 or 3 vertex model – as in the previous challenges, there may be „suggestions” from various quarters to minimize the use of the model. I believe that the project leader should make the final decision. He can and should consult it, but it should be his decision that should be binding – he is the one, who has the best view of all the actions carried out in the project, that ultimately lead to the minimization of risks.

This model can be applied to any R&D activity. However, given the nature of radical and disruptive innovation projects, I believe it is an essential tool, that every project manager should use. Where the aim of the project is not only to deliver a new product to the portfolio, but also to acquire and capitalize on the knowledge, that will be needed in the later stages of acquisition and mass production.

-

[…] Building hypotheses and confirming them […]

LikeLike

Leave a reply to The concept of the ideal solution as the starting point for the project – R&D Coach Cancel reply